A Tanzanite Experience

Share

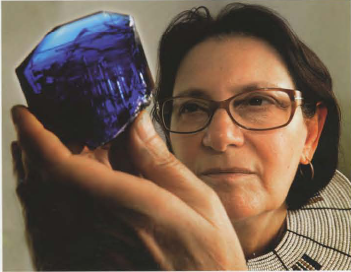

Written by Naomi Sarna – Originally published to gemalytics.com – In March of 2012, I had the great good fortune to be invited by Hayley Henning, Executive Director of the Tanzanite Foundation to go to Tanzania, pick out gem tanzanite and carve it for the IU Awards International Competition in Hong Kong. It was hoped that the carving would win a prize and then be sold, the proceeds to benefit the group of Maasai who live near the Richland Resources mine, Tanzanite One. Deborah Yonick has previously written about the mine and the gorgeous trichroic mineral found there, the only place on earth where tanzanite is found.

The government of Tanzania forbids the export of rough tanzanite larger than 1 gram, and the competition stipulated that the gem carvings could not be larger than 80 grams. The only way to obtain rough of a substantial size was to go to the mine and carve it there. What a wonderful adventure, I thought. While I was there, I would also be teaching a group of Maasai women to wire wrap lower grade tanzanite to sell in tourist shops. These wonderful people are greatly impoverished, no electricity, no eyeglasses, very little fresh running water. I assumed this would be an excellent project for them as they already are highly skilled in making beaded ornaments. I took 35 various pliers, miles of wire and various findings. When we met, they had no idea what pliers were or what one did with them but they quickly learned and they made beautiful jewelry which will soon be auctioned on at the Munich Specimen and Mineral Show, and Liquidation Channel in Texas, to their benefit.

Right away I was given a 200 gram natural, unheated crystal specimen. I said that this was such a beauty that it would be a shame to carve it. However, it was the only piece of quality material available at that time and so I began to carve it. Time was of the essence; I had to carve the material enough for it to qualify for export as an art object and I only had a few days to do the carving.

The circumstances under which I was carving would make any carver cringe. I had brought my carving arbor and an AC-DC converter which worked sometimes, as the electricity was intermittent. My table-top was the opened closet bottom of cabinets, filled with rubble from construction. Because of the size of the shield, I did not bring my water shield and instead used a plastic 5 gallon water bottle which I cut and taped to accommodate my carving arbor and my hands. Interesting.

Light was another challenge. Flashlights were offered but finally enough lamps were provided that I was able to work.

Tanzanite is found in graphite. Miners come up coated in the black, slippery mineral. The rough I was cutting had a large inclusion of graphite which I rapidly removed, creating a vertical groove in the piece.

The question arose: would I cut into the natural termination or leave it? This rough was sceptered with a perfect trichroic crystal, fabulous blue on the A axis, blue-violet on the B axis. I taped the crystal termination protect it and then carved away to see what developed.

It’s easy to write about carving a piece when things go well – the piece carves itself, polishing becomes perfection. However, there are times in the life of any carver when no matter what you do, go left or right, up or down, back or forward, when nothing you do is the right thing. This is a story about when everything went wrong. I do not generally subscribe to the idea that gems hold magical properties, but this piece did not want to be carved and fought me every inch of the way!

There are very few, if any, A grade tanzanite carvings, so reference to past experience did not exist. No one seemed to know that the inclusions were long rectangular cells filled with mild sulphuric acid. I had barely time to examine the material before I had to start carving it so I neglected to take into account the numerous cell inclusions, or their nasty nature. I had to decide quickly if I was going to leave the openings or fill them with some epoxy filler. I decided to leave them as expressions of the natural material.

The sulphuric acid was making my plated diamond bits peel quickly and the skin on my hands was suffering terribly also. I thought to neutralize the acid with baking soda, which worked but created another problem: the rough became very slippery and so I quickly stopped that experiment.

Tanzanite, which is a variety of zoisite, has a Mohs hardness of 6.5 – 7.5 and my experience carving opal, of similiar hardness, made me think that carving would be easy and polishing a problem. Again, I was wrong. The tanzanite was soft but very brittle and splintered frequently, making another problem for my hands which were frequently slivered and bled. Using using rubber wheels with silicon carbide worked best and as fast as diamond bits.

Many gems are a little forgiving when they get a bit warm. Not tanzanite! The slightest hot spot made a rainbow and fractured. I used tepid water and persevered.

Because quartz is mixed with the zoisite, there are soft and hard spots which are side by side. In almost every gem, the change from hard to soft or between colors is a danger area for cracking or splintering. In the sceptered long part there were frequent blocks of differing colors and hardness. Chunks fell off and there were many splinters. Finally the worst occurred; the piece broke at the middle. I thought I would faint.

I was seriously involved with making this piece the very best I could as I wanted to be able to sell it to help my Maasai friends and when the piece broke I felt that I had ruined something which could be of benefit to them. I wanted to cry. Perhaps I did.

Ok. Next. I epoxied it back together and continued. There were spots I didn’t like and tried to cut through them to create a more beautiful line. It was bizarre. It seemed that I kept returning to the same shape over and over, only smaller as I cared the precious material away. I could not get it to shape up the way I wanted.

Time was getting very short. I had to start polishing, another challenge. The rubber wheels were pretty good for smoothing the surface and I was using medium felts, not the hard or rock hard as they chipped the piece just as the wooden wheels did. I used silicon carbide, lots of water and a slowish speed to avoid any heat build-up. On larger areas I went to very worn Nova wheels which were ok.

Finally, very slowly I used large medium and hard felts, sometimes wooden wheels I made myself and diamond. I used the wooden wheels to maintain the crispness of the open cells as I wanted them to stand out and not be observed as poor polishing. The felts softened the edges of the cells, which I did not want and thus used the wooden wheels. Sometimes it just got hot and that was that. Back to the rubber wheels to remove the spot. Diamond up to 14,000 and then a touch with the 50,000.

The stand was a continuation of the flowing shape I had carved, cast in silver and blackened it with liver of sulphur to represent the black graphite the gem was found in. I embellished it with silver satin polished fins to represent the wind from the Rift Valley. The piece represented, to me, as I was carving it, a Maasai woman, her kangas (the skirts and wraps) flowing in the wind. The uncarved natural termination became Mount Kilimanjaro which is on the traditional Maasai land in in constant view of the tanzanite mine. I named it Maasai Skies.

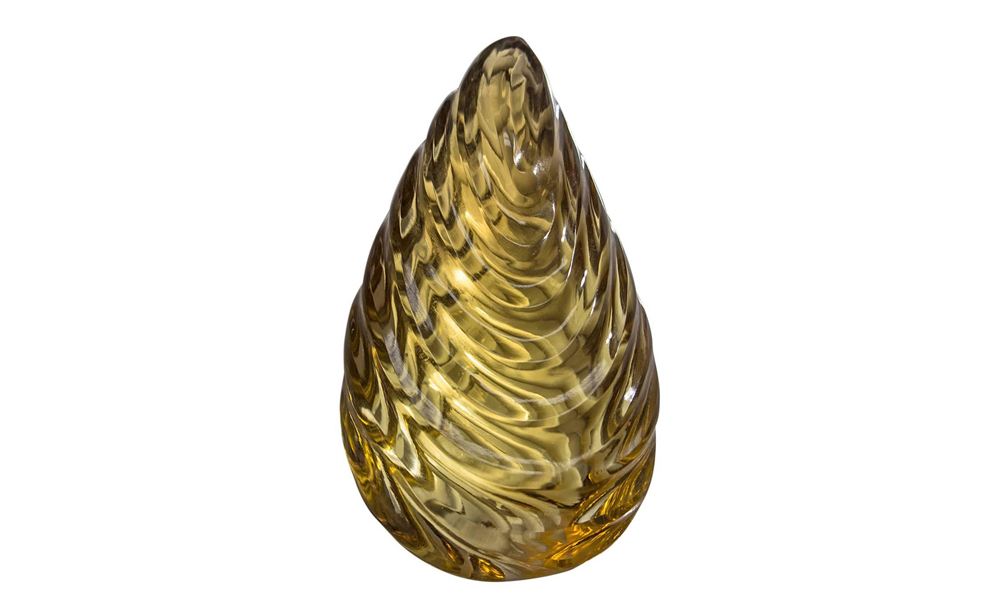

Although this was a carving that filled me with despair, it was a Finalist at the IU Awards Competition and I look forward to selling it and sending the proceeds to the wonderful Maasai. While I was at the mine I was given another 300-gram piece of rough which I had to carve with lightning speed for the same export reasons. This piece caused me much less aggravation, first because I was now familiar with tanzanite’s nature and also because this piece did not fight me as the other one had done. Completed, it may be the world’s largest tanzanite carving, finishing at about 150 grams and named L’Heuere Bleue – the moment when the evening sky turns that wonderful rich blue-violet. This piece is currently in the AGTA Spectrum Awards Competition and I am hopeful that it will be a winner, and the benefits of sale also go to the Maasai of Tanzania.

![Mount Kilimanjaro /ˌkɪlɪmənˈdʒɑːroʊ/,[6] with its three volcanic cones, "Kibo", "Mawenzi", and "Shira", is a dormant volcano in Tanzania.](https://naomisarna.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/Tanzania.jpg)